Balanced Scorecard in Higher Education Institutes

The purpose of this paper is to show how the Balanced Scorecard approach, a performance management system, could be implemented at institutes of higher education. Balanced Scorecard is a strategic weapon for all organizations including Educational institutes and especially institutes of higher education. The implementation of the BSC approach is presented. This paper tries to study use of BSC in various universities across the globe, the various approaches and perspectives used with examples; its use in Indian environment is also studied. The paper points out that the BSC approach is well suited to a higher education situation esp. for aligning various perspectives with strategy of the organization. Recommendations are given for the use of BSCs effectively for improving institutional performance.

Educational institutions are now experiencing the need to adopt the concepts that they have taught. Increased competition, globalization, technology and resource constraints are making institutions rethink their processes in order to ensure value adding processes are in place to ensure success. Also recently a lot of strong criticism of business education’s relevance to business and the community in general has been made (Bennis and O’Toole, 2005; Holstein, 2005). The institutes are also unable to measure how much, value is added by their programs and this only aggravates the problem (Pfeffer and Fong, 2002). With the rising competition in the environment, there has been quite a critical discussion about the nature, value and relevance of business schools. Howard Thomas (2007) in their research on business schools has pointed out the following critics:

- doing irrelevant research;

- being too market-driven and pandering to the ratings;

- failing to ask important questions;

- pursuing curricular fads;

- “dumbing down” course content; and

- focusing more on specialist, analytical rather than professional managerial skills

This increased criticism and competition, has made it is important for business schools, to have a clear strategy, strategic positioning and alignment to the competitive environment. They need not only to answer the strategic question concerning what kind of business school they want to be (e.g. on a continuum from internationally prestigious and research-oriented to professionally focused and applied), but also set suitable performance goals and policies to attain these goals and incessantly monitor and adapt strategy and strategic positioning when weak performance signals are observed.

It is thus more important than ever to develop and measure processes that lead to successful outcomes. This brings into focus the measures of performance as well as the process that need to be put in place to ensure that the areas of concern are addressed. The thing that makes the concept of performance management more special is that various initiatives are systematically linked together in a conscious and planned way to align as much organizational activity as possible with the intended strategy.

The Balanced Scorecard Concept

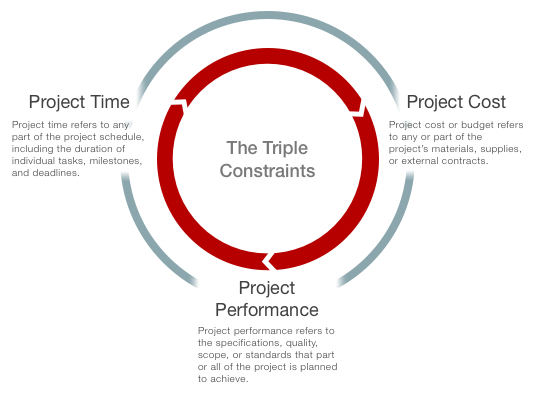

The ‘Balanced Scorecard’ (BSC) concept was formulated by Robert Kaplan and David Norton and was most notably described in a Harvard Business Review article (Kaplan & Norton 1992). The widespread adoption and use of the BSC in business is well documented. The basic premise of the BSC is that financial results alone cannot capture value-creating activities. Kaplan and Norton (1992) suggested that organizations, while using financial measures, should develop a comprehensive set of additional measures to use as leading indicators, or predictors, of financial performance. They suggested that measures should be developed that address the following four organizational perspectives:

- Financial perspective: “How should we appear to our stakeholders?” – uses traditional financial measures to measure past performance.

- Customer perspective: “How should we appear to our customers?” – focuses on stakeholder satisfaction and the value propositions for each stakeholder.

- Internal business processes perspective: “What processes must we excel at?” – refers to internal organizational processes.

- Learning and growth perspective: “How can we sustain our ability to change and improve?” – looks at intangible assets such as employee knowledge and organizational cultural attitudes for both individual and organizational self-improvement.

All of the measures in the four perspectives must be aligned with the organization’s vision and strategic objectives, enabling managers to monitor and adjust strategy implementation leading to breakthrough performance (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). The BSC provides a way of organizing and presenting large amounts of complex, interrelated data to provide an overview of the organization and foster effective and efficient decision making and continuous improvement. Developing the BSC requires the identification of several key components of operations and financial performance, establishing goals for these components, and then selecting measures to track progress toward these goals.

Literature Review

Although the concept of the BSC has been widely adopted and used in the business sector, the education sector apparently has not embraced the BSC concept widely, as indicated by the dearth of published research on this topic. A thorough review of the literature yielded few significant publications. The dearth of literature available for the topic points to the fact that BSC has not found great acceptance in the education industry. Bailey et al. (1999) surveyed business school deans’ opinions about the potential useful measurements for a balanced scorecard. Cullen, Joyce, Hassall, and Broadbent (2003) proposed that a balanced scorecard be used in educational institutions for reinforcement of the importance of managing rather than just monitoring performance. Sutherland (2000) talks about how the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California adopted the BSC to assess it academic program and its planning process. Chang and Chow (1999) reported that 69 accounting department heads were generally supportive of the balanced scorecard’s applicability and benefits to accounting programs. Papenhausen and Einstein (2006) revealed how BSC could be implemented at a college of business. Armitage and Scholey (2004) successfully applied the BSC to a specific master’s degree program in business, entrepreneurship and technology.

In higher education, there are certain conventions in this regard that are acceptable as a measure of excellence. Higher education has emphasized academic measures, rather than emphasizing financial performance. These measures are usually built on and around such aspects as faculty/student numbers (ratios), demographics; student pass percentages and dispersion of scores; class rank, percentile scores; graduation rates; percentage graduates employed on graduation; faculty teaching load; faculty research/publications; statistics on physical resource (see library, computer laboratories etc.). Ruben (1999) indicates that one area deserving greater attention in this process of measurement is – the student, faculty and staff expectations and satisfaction levels.

In a study conducted by Ewell, (1994) (cited in Ruben, 1999), the measures used in 10 states in the USA to report performance of higher education institutions, were as under:

- Enrollment/graduation rates by gender, ethnicity and program.

- Degree completion and time to degree.

- Persistence and retention rates by gender, ethnicity and program.

- Remediation activities and indicators of their effectiveness.

- Transfer rates to and from two and four year institutions.

- Pass rates on professional exams.

- Job placement data on graduates and graduates’ satisfaction with their jobs.

Some of the problems associated with the use of the BSC in education arise from the different perspectives and needs that have to be addresses. Norreklit (2000) pointed out, that the perspectives in this case are interdependent and part of a linear cause and effect chain. McAdam and O’Neil have said that it is difficult to balance the different perspectives and this has to be carefully considered when designing the BSC.

Tertiary Education in India

In India, the University system, as we see today, originated about a century and half ago with the establishment of universities at Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, Allahabad and Lahore between 1857 and 1902. These were modeled after the British Universities of that period. The Central Advisory Board of Education’s (CABE) Committee on Autonomy of Higher Education Institutions (2005) in its report states that currently the Indian higher education system consists of 343 university level institutions and about 16,885 colleges and that there are many nagging concerns about its role and performance. Many of our reputed universities and colleges have lost their pre-eminent positions. Only a few manage to maintain their status and dignity in an environment of complex socio-economic pressures and worldwide changes in approaches to the educational processes. Under the rapidly expanding situation with multiplicity of expectations from the higher education system, it has become necessary to identify those attributes, which distinguish a first-rate institution from a mediocre one.

The complex array of associated issues deserves a total rethinking of our approach to higher education. Serious efforts are now underway to develop the policy perspectives in education involving deeper national introspection and fundamental changes in the structure, content and delivery mechanisms of our university system. The report further indicates that the enrollment in the Indian higher education system has increased from 7.42 million in 1999-2000 to about 9.7 million at present, indicating nearly 10 percent annual growth. The colleges account for about 80 percent of the enrollment with the rest in the university departments. Thus the programmes available in the college system largely determine the quality of our higher education. In the past decade there has been a sharp increase in the number of private colleges as well as universities with the status of either deemed to be universities or state universities. The proportion of eligible age group wishing to enter higher educational institutions will most likely increase significantly from the present level of about 7 per cent. The regulatory mechanisms will perhaps be liberalized. Higher education is continuing to expand, mostly in an unplanned manner, without even minimum levels of checks and balances. Many universities are burdened with unmanageable number of affiliated colleges. Some have more than 300 colleges affiliated to them. New universities are being carved out of existing ones to reduce the number of affiliated colleges. Under these circumstances, our dependence on autonomy as the means to improve quality of such a huge size of higher education system poses serious challenges.

Venkatesha (2003 as cited in Venkatesh & Dutta, 2007) compares and finds a lot of differences in the work-culture between the teachers of postgraduate departments of universities with those of colleges. In degree colleges, teaching is the only mandate and pertaining to this, teachers have to improve their knowledge in teaching by undergoing orientation and refresher courses, summer-camps, workshops and participating in seminars/symposia from time to time. On the basis of these activities, teachers are considered for promotion to the next cadre. Some college teachers, who are interested in research may conduct research and publish papers. Research activity of college teachers is invariably out of their natural interest rather than a yardstick for their promotion unlike in universities. Once a university teacher acquires a PhD degree, many university teachers lapse into routine teaching assignments. Because of this type of dual role of teaching and research without defined guidelines, university teachers can neglect either teaching or research, or sometimes both. In Indian universities, teachers are promoted based on their research publications, books written, papers presented in seminars/symposia, membership of various academic societies, etc., but much importance has not been given to the teachers’ contributions towards teaching.

This type of situation in our universities tempts many teachers to neglect teaching and take up some sort of research mostly uneconomical, unproductive, outdated and repetitive type and venture into the business of publishing substandard research articles. The system normally recognizes quantity like number of PhD students guided, number of papers published, etc. rather than quality of the research and publications. Unfortunately, no concrete method has been developed so far to judge the teaching and research aptitude of university teachers. Some academicians argue that both teaching and research cannot be done at the same point of time. However, it is generally thought that education (even from undergraduate level) and research should coexist to complement each other. Special emphasis on assessment-oriented teaching and research will impart a new dimension to the role of the teacher.

Commenting upon the inherent contradictions in higher education and research in sciences, Chidambaram (1999) indicates towards a peculiar situation existing in the country. Wherein on one hand a large number of people are being given post-graduate degrees in science disciplines, without an appreciation of their possible future careers; on the other hand, there is a considerable reduction in the number of such talented and motivated students seeking admissions to science courses. The dilution of resources that this irrelevant training represents has the consequence of deteriorating the quality of the training for the really talented people.

Staying on with science education, Narlikar (1999) identifies – poor methodology of science teaching that encourages rote learning, ill-equipped teachers and labs, lack of inspirational and committed teachers, poorly written text-books, peer pressure to join lucrative courses; as some of the causes of the current sickness that has afflicted the science scenario. The romance of science and a proper and correct image is just not getting projected by our institutions or the universities. In his opinion this unfortunate trend can be reversed if the society displays a will and creates an environment to cure the causes of the deeply entrenched malady.

Altbach (2005) provides an overview of the ailments afflicting the higher education machinery in India when he says that India’s colleges and universities, with just a few exceptions, have become “large, under-funded, ungovernable institutions”. Many of them are infested with politics that has intruded into campus life, influencing academic appointments and decisions across levels. Under-investment in libraries, information technology, laboratories, and classrooms makes it very difficult to provide top-quality instruction or engage in cutting-edge research. Rising number of part-time and ad hoc teachers and the limitation on new full-time appointments in many places have affected morale in the academic profession. The lack of accountability means that teaching and research performance is seldom measured with the system providing few incentives to perform. He goes on to say that India has survived with an increasingly mediocre higher education system for decades.

Now as India strives to compete in a globalize economy in areas that require highly trained professionals, the quality of higher education becomes increasingly important. So far, India’s large educated population base and its reservoir of at least moderately well-trained university graduates have permitted the country to move ahead. He concludes that the panacea to the ailments of Indian universities is an academic culture based on merit-based norms and competition for advancement and research funds along with a judicious mix of autonomy to do creative research and accountability to ensure productivity. He rightly says that “world class universities require world class professors and students – and a culture to sustain and stimulate them”. He recommends a combination of specific conditions and resources to create outstanding universities in India including sustained financial support, with an appropriate mix of accountability and autonomy; the development of a clearly differentiated academic system – including private institutions – in which academic institutions have different missions, resources, and purposes, managerial reforms and the introduction of effective administration; and , truly merit-based hiring and promotion policies for the academic profession, and similarly rigorous and honest recruitment, selection, and instruction of students.

Misra (2002) identifies “management without objectives” as one of the key reasons of the downfall of the Indian university system. He highlights the need for – adopting a functional approach in our universities; periodic academic audits; greater autonomy and accountability in all spheres of operations; open door policy welcoming ideas and people from all over; administrative restructuring decentralizing university departments and schools; and making education relevant to our people and times; as the basic steps in improving the Indian universities. The above discussion establishes the need for accountability based autonomy and being consistently relevant to the context in which the Indian universities (or any other university anywhere for that matter) may exist. This creates the backdrop for adopting the basic tenets of strategic management in the paradigms of operating our universities. The balanced scorecard is one such basic tool that can certainly be of assistance in this rationalization process.

Application of Balanced Scorecard at Institutes of Higher Education

There are a number of universities around the world that have implemented the Balanced Scorecard. They have modified the perspectives to suit their needs.

Balanced Scorecard at the University of Minnesota

Their mission statement is to prepare students to become managers and leaders who will add value to their organizations and communities by:

- offering high quality graduate and undergraduate programs;

- conducting valuable basic, applied and pedagogical research; and

- Supporting regional economic health and development.

Based on this mission, The BSC strategy map was developed with three overarching and complementary strategic themes:

- Teaching themes – selection and retention of faculty who are focused on teaching excellence to gain an increased market share of the educational market.

- Research themes – identification of college faculty as dedicated research colleagues desiring to be champions in their chosen field.

- Outreach themes – use of college faculty to support regional education and other intellectual support.

The BSC strategy map for the college uses a generic architecture to describe each strategy. In this way, each measure is rooted in a chain of cause-and-effect logic that connects the desired outcomes from the strategy with the drivers that will lead to the strategic outcomes.

Linkages between Balanced Scorecard Perspectives

The strategy map illustrates how intangible assets are transformed into tangible customer and financial outcomes. Even though the number of measures in each perspective varies, it is important that each measure align with the organization’s strategy. The measurements used are adapted from Bailey et al. (1999) but were tailored to apply to the college of business.

Financial perspective: The financial perspective contains the tangible outcomes in traditional financial terms.

Stakeholder perspective: Value propositions are created to meet the needs of each stakeholder. These value propositions are those that hold the greatest value to each stakeholder and represent outcomes of the college’s internal processes. Satisfactory realization of the value propositions translate into financial outcomes outlined in the financial perspective.

Internal process: The internal process perspective describes the critical internal processes that drive the stakeholder satisfaction and the college’s financial outcomes. Internal business processes deliver the value proposition to stakeholders and drive the financial effectiveness.

Learning and growth perspective: The learning and growth perspective identifies the sets of skills and processes that drive the college to continuously improve its critical internal processes. The learning and growth areas that feed into internal processes subsequently drive stakeholder satisfaction and ultimately financial outcomes.

University of California, San Diego

Chang and Chow (1999) indicated that in 1993 the University of California, San Diego’s senior management launched a Balanced Scorecard planning and performance monitoring system for 30 institutional functions using three primary data sources: 1) UCSD’s internal financial reports; 2)National Association of College and University Business Officers benchmarks; and 3) faculty, staff and student customer-satisfaction surveys.

This exercise was conducted under the framework of the university’s vision, mission, and values. Reported benefits and outcomes to date have included reorganization of the workload in the vice chancellor’s area, revision of job descriptions with performance standards, introduction of continual training for user departments, ongoing customer assessments and increased responsiveness to communication needs through the use of technology. O’Neil and Bensimon (1999) described how a faculty committee at the Rossier School of Education of USC adapted a Balanced Scorecard model originally developed for business firms to satisfy the central administration’s need to know how they measure up to other schools of education. The format of the Balanced Scorecard adapted by the faculty included the following four perspectives:

- Academic management perspective (How do we look to our university leadership?);

- The internal business perspective (What we excel at?);

- The innovation and learning perspective (Can we continue to improve and create value?);

- The stakeholder perspective (how do students and employers see us?).

O’Neil and Bensimon (1999) indicated the following favorable results from the academic scorecard implementation:

- Easier approach for the university to accomplish its strategic goals.

- A systematic and consistent way for the provost’s office to evaluate performance reports from various schools and departments.

- The scorecard established common measures across academic units that have shared characteristics.

- The simplicity of the scorecard makes it easier for academic units to show how budget allocations are linked to the metrics of excellence.

University of Wisconsin

The University of Wisconsin—Stout provides a distinct array of programs leading to professional careers focused on the needs of society. Some unique characteristics include the following:

- More than half of the 27 undergraduate programs are not offered at any other campus in the University of Wisconsin system, and several are unique in the nation;

- The programs emphasize business-relation processes and staying current with fast-changing technology and market dynamics; and

- Traditional instruction is reinforced by extensive technology laboratories and industry partnerships.

The university’s programs also include the following key student requirements and corresponding measures or indicators:

- Cutting-edge, career-oriented programs (number of new programs, placement success);

- High-quality, active-learning education (percentage of lab instruction and faculty contact);

- Effective student support services (retention, academic success, student satisfaction); and

- Related employment and academic or career growth opportunities (placement in major, graduate success, employer satisfaction; (Karathanos and Karathanos, 2005).

Kenneth W. Monfort College of Business

The Kenneth W. Monfort College of Business (2004) at Northern Colorado’s mission is to deliver excellent undergraduate business programs that prepare students for successful careers and responsible leadership in business. Some of its unique characteristics follow:

- Pursuing excellence in undergraduate-only business education, uniquely among its regional and national peers;

- One of five undergraduate only programs nationally to hold Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business accreditations in business and accounting; and

- Commitment to a program strategy of high-touch, wide-tech, and professional depth to make the college of business a value leader compared with its competition.

In addition, the programs have the following key strategic objectives and corresponding measures or indicators:

- Build a high-quality student population (average ACT score of new freshmen and average transfer student GPA);

- Maintain high-quality faculty (overall percentage of faculty academically and or professionally qualified);

- Maintain adequate financial resources (available state funds and available private funds); and

- Develop market reputation consistent with program excellence (college of business media coverage; Kenneth W. Monfort College of Business, 2004).

Applicability and Design of BSC in the Indian Environment

Review of extant literature indicates that business organizations, as well as academic institutions, are fundamentally rethinking their strategies and operations because of changing environment demanding more accountability. The BSC is described as a novel approach to face these challenges (Dorweiler and Yakhou, 2005). The strategies for creating value in education need to be based on managing knowledge that creates and deploys an organization’s intangible assets. The scorecard defines the theory of the business on which the strategy is based hence the performance monitoring can take the form of hypothesis testing and double-loop learning. A good BSC should have a mix of outcome measures and performance drivers (Kaplan and Norton, 1996). Marketing and communication strategies vis-a` -vis institutions of higher education assume greater import as the image portrayed by these institutions plays a critical role in shaping the attitudes and perceptions of the institution’s publics towards that institution (Yavas and Shemwell, 1996). In India, for instance, institutions of higher education are becoming increasingly aggressive in their marketing activities. In this increasingly competitive environment, the marketers of higher education should be concerned about their institution’s positioning and image.

The marketing of educational programmes has attracted attention of researchers who have identified research-based planning and programme development, relationship marketing and non-traditional methods for education delivery as key areas for future focus (Hayes, 1996).

Some of the reasons for marketing of higher education gaining importance in the management of higher education programs and institutions are – the founding missions being found increasingly ill-suited for the demands of the marketplace; budgets becoming excruciatingly tight while departments and programmes clamoring for more support; the recruiting and fund-raising arenas having become extremely competitive as well as hostile; higher education being more and more dominated by many largely undifferentiated colleges and universities offering similar programmes; demographic shifts in the operating environment marked by diminishing numbers of traditional full-time students, fewer full-pay students and fewer residential students; escalating demand for adult higher-education and continuing and special-focus programmes; and last but not the least, the sharp rise in the cost of higher education (Kanis, 2000). In India too recently as liberalization has progressed, although in fits and starts, governmental support to institutions of higher learning in the form of grants and subsidies, is drying up. The movement of self-sustenance is gaining force. This also adds up and forces managers of educational institutions, especially in the public domain, to re-think their mission and strategies (Venkatesh, 2001).

Ruben(2004) says that students are affected not only by the teaching environment but also by the learning environment, which includes facilities, accommodation, physical environment, policies and procedures, and more importantly, interpersonal relations and communication and from every encounter and experience. Hence the faculty, staff and administrators have to set good examples by their deeds and recognize that everyone in an institution is a teacher. A wide range of stakeholders and their diverse claims/interests and objectives have to be addressed in the context of the institution of higher education in India. The customer perspective is supposed to aim at the immediate needs and desires of the students, parents, faculty and staff, alumni, the corporate sector and the society at large. It is relevant here to state that looking at students solely as customers becomes a sort of a misnomer as they are also (if not only) the “throughput” that eventually gets processed in the institution and ends up accepted (or rejected) at the verge of graduation. Hence the corporation and society at large should be considered as the real customers.

The second component involves the internal business or operations perspective. This inherently focuses on the implementation and delivery of the academic, research and other programs by the institution and the degree of excellence achieved in the same. The innovation and learning perspective of the organization looks at the development of faculty and staff as a precursor and foundation to excellence in program design and delivery. Finally, the fourth component constitutes of the financial performance and its measure. It is clear in the Indian context especially, that the government although eschews the “profit” word for educational institutions, however is emphasizing more and more on self-sustaining programs and institutions as a desirable outcome of the strategies and models envisaged and pursued by universities and colleges. Surpluses are important as only then institutions can look for achieving greater autonomy in designing and delivering ever new courses and programs that are relevant to the population in context, but expensive to implement.

Kaplan and Norton (1996) say that companies are using scorecard to:

- Clarify and update vision and strategic direction;

- Communicate strategic objectives and measures throughout the organization;

- Align department and individual goals with the organization’s vision and strategy;

- Link strategic objectives to long term targets and annual budgets;

- Identify and align strategic initiatives;

- Conduct periodic performance reviews to learn about and improve strategy; and

- Obtain feedback to learn about and improve strategy.

All the above benefits are relevant in the context of the institutions of higher learning in India. As Pandey (2005), indicates – “a good aspect of BSC is that it is a simple, systematic, easy-to-understand approach for performance measurement, review and evaluation. It is also a convenient mechanism to communicate strategy and strategic objectives to all levels of management”. According to Kaplan and Norton (2001) the most important potential benefit is that BSC aligns with strategy leading to better communication and motivation which causes better performance. Considering the linkages in service management profit chain (Heskett et al., 1994 cited in Kaplan and Norton, 2001) we can say that the potential benefits can be:

- Investments in faculty and staff training lead to improvements in service quality;

- Better service quality leads to higher customer (stakeholder) satisfaction;

- Higher customer satisfaction leads to increased customer loyalty; and

- Increased customer loyalty generates positive word of mouth, increased grants/revenues and surpluses that can be inserted into the system for further growth and development.

With growing popularity for Indian Engineers and graduates in job employment abroad, India has to build world-class quality into higher education. In fact, a critical test of a scorecard’s success is its transparency: from the 15-20 scorecard measures, an observer is able to see through the organizations corporate strategy (Kaplan and Norton, 1993).

Conclusion

In this paper we propose that in an environment that demands increasing accountability from business schools, the BSC Approach offers a promising and valuable tool for implementing a strategic performance management system in institutes of higher education. The top management should focus on strategic themes instead of merely relying on formal structures in institutes. The strategy of the institute/university should be communicated to everyone in a easy to understand language. The roles of teachers, administration staff, deans and others should be clarified in advance so as to implement Balanced Scorecard. We propose that BSC will improve communication in institutes as well as work as feedback mechanism for all concerned. This will result in flawless communication and relatively easy implementation of institutional strategy. We also propose to use BSC for balancing internal as well as external perspectives, as so to foster institutional performance.

So, if Higher education institutions apply the BSC to their organization they will be able to position their students and programs positively in the minds of the international audience.

References

Altbach, P.G. (2005), Higher education in India, The Hindu, Tuesday, 12 April.

Armitage, H. and Scholey, C. (2004), Hands-on Scorecarding, CMA Management, 78 (6) 34-38.

Bailey, A., Chow, C. and Haddad, K. (1999), Continuous Improvement in Business Education: Insights from the For-Profit Sector And Business Deans, Journal of Education for Business, 74 (3),165-80.

Bennis, W., O’Toole, J. (2005), How Business Schools Lost their Way, Harvard Business Review, May, 96-104.

CABE (2005), Autonomy of Higher Education Institutions, Department of Secondary and Higher Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, New Delhi.

Chang, O. H., & Chow, C. W. (1999). The Balanced Scorecard: A Potential Tool for Supporting Change and Continuous Improvement in Accounting Education. Issues in Accounting Education, 14, 395–412.

Chidambaram, R. (1999), Patterns and Priorities in Indian Research and Development, Current Science,77 (7), 859-68.

Cullen, J., Joyce, J., Hassall, T., & Broadbent, M. (2003). Quality In Higher Education: From Monitoring to Management, Quality Assurance in Education, 11, 1–5.

Dorweiler, V.P. and Yakhou, M. (2005), Scorecard for Academic Administration Performance On The Campus, Managerial Auditing Journal,20 (2), 138-144.

Hayes, T. (1996), Higher education marketing symposium wins top grades, Marketing News, 30 (3), 10-11.

Holstein, W.J. (2005), Are Business Schools Failing the World?, The New York Times, 19 June, BU 13.

Kanis, E. (2000), Marketing in Higher Education is a Must Today, Business First, 16 (25), 55.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The Balanced scorecard—Measures that drive Performance. Harvard Business Review, 70, 71–79

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1993), Putting the Balanced Scorecard to Work, Harvard Business Review, September-October, 134-42.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management system. Harvard Business Review, 74(1), 75–85.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (2001), Transforming the Balanced Scorecard from Performance Measurement to Strategic Management: Part I, Accounting Horizons, 15 (1), 87-104.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (2004), How Strategy Maps Frame an Organization’s Objectives, Financial Executive, March/April, 40-45.

Karathanos, D., & Karathanos, P. (2005). Applying the Balanced Scorecard in Education. Journal of Education for Business, 80, 222–230.

Kenneth W. Monfort College of Business. (2004). Kenneth W. Monfort College of Business 2004 Baldrige application summary.

Misra, R.P. (2002), “Globalization and Indian universities – Challenges and Prospects”,

unpublished speech, Third Dr Amarnath Jha Memorial Lecture, Lalit Narayan Mithila University, Darbhanga, Bihar, 2 September.

Narlikar, J.V. (1999), No Fizz and Spark – Decline In Science Education, Times of India, 6 May, 10.

Norreklit, H. (2000) The Balance of the Balanced Scorecard – A Critical Analysis of Some Assumptions, Management Accounting Research, 11 , 65-88.

O’Neil, H., Bensimon, E., Diamond, M. and Moore, M. (1999), Designing and Implementing an Academic Scorecard, Change, 31 (6), 32-40.

Ruben, B.D. (1999), Toward a Balanced Scorecard of Higher Education: Rethinking the College and Universities Excellence Framework, Higher Education Forum – QCI Center for Organizational Development and Leadership, Rutgers University, Camden, NJ.

Pandey, I.M. (2005), Balanced Scorecard: Myth and Reality, Vikalpa,30 (1), 51-66.

Papenhausen, C. & Einstein, W. (2006), Insights from the Balanced Scorecard:Implementing the Balanced Scorecard at a College of Business, Measuring Business Excellence, 10(3), 15-22.

Pfeffer, J., Fong, C. (2002), The End of Business Schools? Less Success than Meets the Eye, Academy of Management Learning & Education, 111 (2), 78-95.

Ruben, B. (2004), Pursuing Excellence in Higher Education: Eight Fundamental Challenges, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Sutherland, T. (2000, Summer). Designing and Implementing an Academic Scorecard. Accounting Education News, 11–13.

Thomas, H. (2007), Business School Strategy and the Metrics for Success, Journal of Management Development, 26 (1), 33-42.

Venkatesh, U. (2001), The Importance of Managing Point-of-Marketing in Marketing Higher Education Programmes: Some Conclusions, Journal of Services Research, 1(1), 125-40.

Venkatesh, U., Dutta, K. (2007) Balanced Scorecards in Managing Higher Education Institutions: an Indian Perspective, International Journal of Educational Management, 21 (1), 54 – 67.

Yavas, U. and Shemwell, D.J. (1996), Graphical Representation of University Image: a Correspondence Analysis, Journal for Marketing for Higher Education, 7(2), 75-84.