Econometrics of France – General overview of the economy, identifying the main aggregate demand components that drive GDP growth

Econometrics – France is acknowledged due to its efforts in fighting poverty and improving employment among the citizens (Ciccone & Jarociński, 2010). The country is comprised of many sectors which work collaboratively to provide services and products to her citizens (Facchini & Melki, 2013). The country has been a member of IBRD since 1945 and was among the first country to receive their loan. The country has a population of over 66.8 million people as per the 2015 report. In overall, the country’s GDP was $2.4 trillion in 2015, which the country reported that it was growing at an annual rate of 1.2%.

Analyzing key econometrics such as GDP may not generally be the most pertinent synopsis of accumulated monetary execution for all economies, particularly when generation happens to the detriment of devouring capital stock (Ciccone & Jarociński, 2010). While GDP gauges in light of the generation approach are for the most part more dependable than assessments incorporated from the pay or consumption side, distinctive nations utilize diverse definitions, techniques, and reporting guidelines (UKDS, 2016). World Bank staff survey the nature of national records information and now and then make acclimation to enhance consistency with worldwide rules. All things considered, noteworthy disparities stay between universal guidelines and real practice (Sly & Weber, 2016).

Numerous measurable workplaces, particularly those in creating nations, confront extreme confinements in the assets, time, preparing, and spending plans required to deliver solid and far reaching arrangement of national records insights. Among the challenges confronted by compilers of national records is the degree of unreported financial action in the casual or optional economy. In creating nations a huge share of farming yield is either not traded (on the grounds that it is expended inside the family unit) or not traded for cash (Sly & Weber, 2016).

Private usage has usually been the driver of money related improvement in France and it coordinated the impact of the fiscal crisis in 2009. Regardless, in 2012, private use contracted unprecedented for over two decades in the aftermath of the crisis, amidst purchaser assurance levels that had debilitated and direct money related improvement rates (Facchini & Melki, 2013; Ciccone & Jarociński, 2010). After government use, which has remained by and large stable in the earlier decade, wander is the greatest portion of France’s budgetary advancement.

Econometrics theory was the GDP portion that was hit the hardest by the fiscal crisis in France and changed wander dove 9% in 2009. Taking after a ricochet back to 1.9% advancement in 2010, hypothesis has lamented starting now and into the foreseeable future and it contracted 0.8% in 2013. Moreover, France is a net shipper, in any case, the outside division littly affects the economy (Ciccone & Jarociński, 2010).

Quickly, organizations are the guideline benefactor to France’s economy, with more than 70% of GDP originating from this section. Immense subdivisions of organizations join the sparing cash and budgetary, security and tourism parts. Creating speaks to somewhat more than 10% of France’s GDP and France is an overall pioneer in the avionics, auto and lavishness stock undertakings (Ciccone & Jarociński, 2010). Disregarding the way that agriculture speaks to around 2% of French GDP, it is seen as a fundamental industry in France and is frequently the beneficiary of government gifts or protectionist plans (Facchini & Melki, 2013).

Econometrics – How well the country has managed to achieve the four macroeconomic objectives of high and stable economic growth, low unemployment, low inflation and avoidance of large balance of trade deficit.

There is a run of the mill see, as regularly as could be expected under the circumstances watched or reported by different economists is that France has a unique approach to her economy and operations. In fact, France is delineated as a something close to a revolt economy, where institutions and different staffs are in frequent strikes especially on matters that affect them collectively (Ciccone & Jarociński, 2010).

Like most myths, the intellectual economy myth – , in light of current conditions, executed by people with a grievance, or by people who have visited the country due to either economic interest or their personal interests. Different economic overviews or rather arguments have come up and each shows different result from the previous For each one of its deficiencies – and its qualities – however, all the economists tend to concur that France economy is healthy and well performing above average especially when compared with the G20 terms (UKDS, 2016).

Changing France is to an unprecedented degree troublesome to the time when some are imparting that nothing not another French resistance is required. According to a 2013 econometrics report by IMF, Hollande government was aiming to to cut down different demands by the French economy (Facchini & Melki, 2013); however this was qualified by a notice that more should be done to cut open spending, instead of raise responsibilities. Hollande has vowed to go basic on costs, to forsake putting any further un-convincing weight on French industry (Sly & Weber, 2016).

The failure of changing the current situation in France, has become one of the primary challenge that is undermining the country from attaining effective budgetting (Facchini & Melki, 2013); However, the approach that the government have left many economists talking, for instance, a 2013 report argued the following statements in regard to the France government.

a) The working hours in most businesses located in France are mostly shorter than the time that European countries work. For instance, when in Germany the average working hours per year are 1904 while in France they are 1679.

b) Most employees in France retire earlier than employees in Germany, the typical retirement age in Germany is 62.3 while in France it is 60.3 and 64 in the United Kingdom.

c) In France, the employees take many events, and holidays off work than employees in Germany and UK do, specifically they take 7 days more than Germans do and 36 days more than British employees do. However, despite all the fact, the France economy remains competitive (UKDS, 2016).

One of the fundamental issues identified with France’s work markets is unmistakable and interminable business district that affiliations end up in when they endeavor to end a man from staff. Many say the fear of putting in two years in a business tribunal is a colossal execute for all the more little affiliations, who are in this way more slanted to spread brief contracts instead of persevering ones. While attempting to settle this Hollander will ensure to past what many would consider workable for a laborer to hold up a disagreeing of out of line dismissal, which starting now remains at two years after they were surrendered.

In an offer to urge boss to contract more staff, Hollande game-plans to offer a “securing prize” to self-representing endeavors. The course of action is to give some place among 1,000 euro and 2,000 euro for every power who is chosen with a remuneration of up to 1.3 times the national scarcest wage. The show is kick-start shrinking by adjusting the gathering coordinated wander holds commitment costs that may startle away executives, with Hollande’s party as to it to be much speedier than changing France’s social obligation laws for low paid labourers (Sly & Weber, 2016).

The report released by the business serve in France exhibited that the strategy approaches will target low-talented authorities, and will especially focus on change divisions, for instance, mechanized and environment. The spending strategy for plan has been connected by 80 million euro in 2016.

The present year’s measures will cost €2 billion, which the mister of reserve said would be “reimbursed in full” by meander holds from elsewhere. Hollande ensured that the measures would not be financed by cost rises.

A blend of fitting optional measures and altered stabilizers has padded the effect of the emergency. The meander force diminishment presented in the 2010 spending course of action is comparably welcome, yet extra spending ought to now be confronted. Laying out and plainly passing on a significant multiyear leave system is a need. The required solidifying addresses a chance to re-adjust open funds by cutting wasteful spending, developing legacy, property and carbon strengths and progress changing the favourable circumstances framework.

Identify and critically analyse 3 economic/political/demographic trends (Econometrics) that the country is experiencing and what the implications of these trends could be in the future.

Demographic trends in France

In 2030, the number of inhabitants in France will achieve 67.9 million, an expansion of 5.8% from 2015 (UKDS, 2016). Moderately high, yet declining, birth and ripeness rates, close by positive net movement, imply that France’s populace will build speedier and age slower than most nations in Western Europe in 2015-2030. France is a standout amongst the most urbanized nations in Western Europe and this will keep on being the situation in 2030 when 91.8% of its aggregate populace will be comprised of urban occupants.

The long haul steadiness of richness and birth rates (right around 800,000 yearly births, regardless of slight falls in 2011 and 2012) implies that the base of the French populace pyramid is still very expansive (Baltagi, 2011)While characteristic increment is still unmistakably positive, the maturing procedure is reflected in a rising number of yearly passing’s as the populace with the most astounding dangers of biting the dust becomes bigger.

The diminishing in first social unions is measured by the entire of rates (total first marriage rate) or the general probability of first marriage. Some place around 1972 and 2012, the total first marriage rate tumbled from 91.7 to 46.6 first social unions for each 100 men and from 94.8 to 47.5 first social unions for every 100 women (Baltagi, 2011). Probability data show a strong decrease in the degree of social unions between never-married individuals up to age 50: it tumbled from 90 first social unions for each 100 never married men in 1972 to 53.5 in 2012, and from 93.4 first social unions for every 100 never-married women to 56.3 for that years

- (i) Estimate the consumption function for your chosen country and comment on your results

Yt = a + bXt

Where Yt is aggregate consumption of the country in year t;

Xt is aggregate income (GDP) of the country in year t;

a is the linear intercept and b is the slope coefficient

[Note Aggregate Consumption (Y) = GC + PC (government consumption expenditure plus Household consumption expenditure) (Year 2015)

Y = 23.9 + 07

= 24.6

(ii) Write the estimated regression equation and comment on the results of the regression analysis

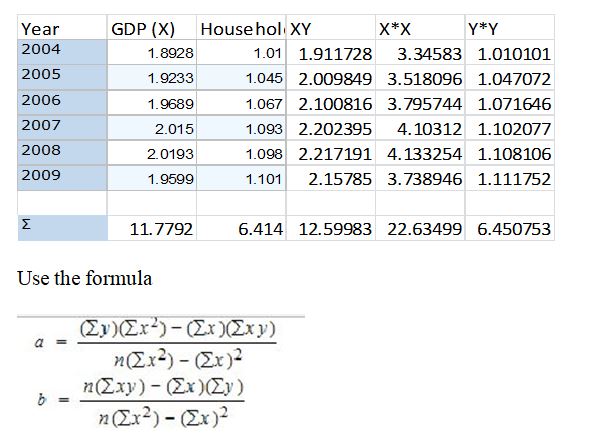

Taking values from the graph, we make a table consisting values of the recent 5 years (Excel Sheet below)

Use the formula

Where a=a and b = b

a = -138.67

b =-515.123n

Insert the values in the equation

Yt = -138.67 – 515.123 Xt

(iii) Calculate the confidence interval for b at 95% confidence interval.

-512 * (1 – 0.95)

CI = 25.6

(iv) Test the statistical significance of b

Exposes the error index

CI – Y

25.6 – 24.6

= 1.0

(v) Test the statistical significance of the model

The values are close to the mean of X have less leverages that outliers towards the edges.

(vi) Identify whether the error terms of the model are autocorrelated and/or heteroskedastic.

The error was auto-correlated, with 1.00 error index, which was explained by the value estimation and rounding off

References

Baltagi, B. (2011). Econometrics (1st ed.). Berlin: Springer.

Ciccone, A. & Jarociński, M. (2010). Econometrics & Determinants of Economic Growth: Will Data Tell?. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(4), 222-246.

Facchini, F. & Melki, M. (2013). Efficient government size: France in the 20th century. EconometricsEuropean Journal Of Political Economy, 31, 1-14.

Sly, N. & Weber, C. (2016). Bilateral Tax Treaties, Econometrics and GDP Co-movement. Review Of International Economics.

UKDS,. (2016). Econometrics UKDS. Stat Metadata Viewer

Relevant Links

Economics Dissertation Topics

Circular Flow Model Economics Report

Did you find any useful knowledge relating to Econometrics in this post? What are the key facts that grabbed your attention? Let us know in the comments. Thank you.